As we approach Memorial Day I believe that it is altogether fitting and proper that we memorialize the gallant warriors that have spilled their blood in the service of our beloved country, lest we forget.

Fritz

THE HISTORY OF THE MEDAL OF HONOR

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is our nation’s highest military award for valor. First authorized in 1861, in the 159 years since, 3,525 Medals of Honor have been bestowed upon American servicemen. The citations for the awards read as a “Who’s Who” of some of the bravest, most selfless, and at times, most sacrificial young men in America’s history. The Medal has a long history, and took many years to become the award held in such high regard as it is today.

In the early months of the American Civil War, the US military had no valor awards which could be given to soldiers or sailors distinguishing themselves in combat. In December 1861, a bill was passed in the Senate to authorize the production and awarding of “medals of honor” in an effort to “promote the efficiency of the Navy.” This first Medal could be awarded to enlisted sailors and Marines only. Thus, the Navy Medal of Honor was created. In February 1862, a similar bill was introduced to create a medal to be awarded to privates in the army who distinguished themselves. Later that year the bill was signed into effect, creating the US Army Medal of Honor.

Today, the Medal of Honor is known to be a rare award representing action of incredible valor or self-sacrifice. However, prior to World War I, the MOH was awarded much more frequently—nearly 3,000 times. Between 1861 and 1918, requirements for awarding the Medal of Honor and who could receive it gradually changed. The most significant changes allowed officers to receive the medal, applied “new standards” which meant the medal could not be awarded for “simple discharge of duty” but had to be for significant acts above and beyond those of others, and the recommendation had to have eyewitness testimony and could not be self-recommended.

In 1890, the Medal of Honor Legion was established with the responsibility of protecting the integrity of the Medal. Twenty-six years later, a Medal of Honor review board was created to review each Army Medal of Honor awarded prior to that year. There were increasing concerns that the Medal was being presented too easily, and that it had often been awarded for events not meriting such honor. After reviewing every Medal awarded until 1916, the review board decided to rescind 911 Medals, including the only one awarded to a woman—Civil War Assistant Surgeon Mary Walker. Walker’s Medal was rescinded due to her civilian status (it was reinstated in 1977 by President Jimmy Carter, making Walker the only female recipient).

A July 1918 Act of Congress laid the foundation for modern American military awards. The act provided for “lesser” awards, such as the Silver Star, thus giving a higher precedence to the Medal of Honor. The act also laid out an important requirement for the Medal: “the President is authorized to present, in the name of the Congress, a medal of honor only to each person who, while an officer or enlisted man of the Army, shall hereafter, in action involving actual conflict with an enemy, distinguish himself conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.” Thus, the Medal of Honor is sometimes referred to as the Congressional Medal of Honor.

During this period, the Army Medal was significantly redesigned. The new design for the medal was done by a recipient from the Civil War, General George Gillespie. This new version of the Medal became the now-iconic star surrounded by a green laurel, suspended from a pale blue ribbon with 13 white stars, and a bar bearing the word VALOR. The Navy Medal underwent only minor redesigns, but also switched to the blue ribbon with 13 stars. The Navy’s Medal has always hung from an anchor.

In World War II, many men went above and beyond the call of duty. There are 473 Medal of Honor recipients from the war. Their citations are full of heroics and sacrifice. Many of the Medals were awarded posthumously, in recognition of a life cut short. One of those is the Unknown Soldier who rests in the Tomb of the Unknown at Arlington Cemetery. The Medal was awarded among all ranks and rates—from Lieutenant General Jonathan Wainwright at the top all the way down to 18 year old Private Joseph Merrell.

![Image]()

![]()

![Image]()

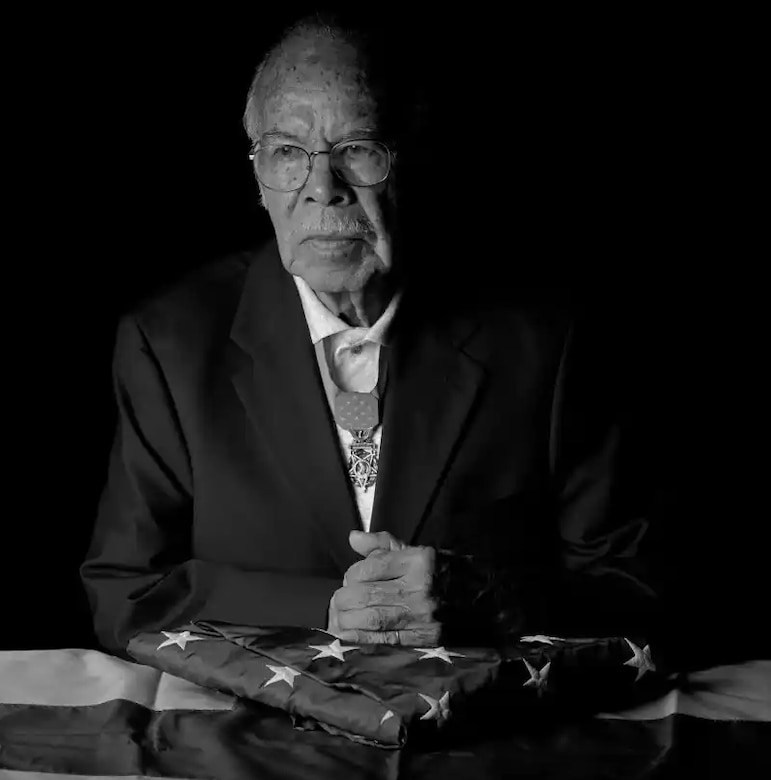

Since the end of World War II, over two dozen Medals have been awarded to men who were denied the Medal during the war due to their race, ethnicity, or religion. In 1997, President Bill Clinton presented the Medal to seven African Americans who had been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Three years later, President Clinton presented 22 Japanese American veterans with the Medal of Honor. They too had been denied the honor during the war. In 2014, President Barack Obama presented the Medal to the “Valor 24,” individuals who had been denied based on race or religion. Of those, seven were World War II veterans. The latest Medal awarded for action in World War II was to US Army First Lieutenant Garlin Conner, whose Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the Medal. His widow, Pauline Conner, accepted the Medal on his behalf from President Donald Trump in 2018.

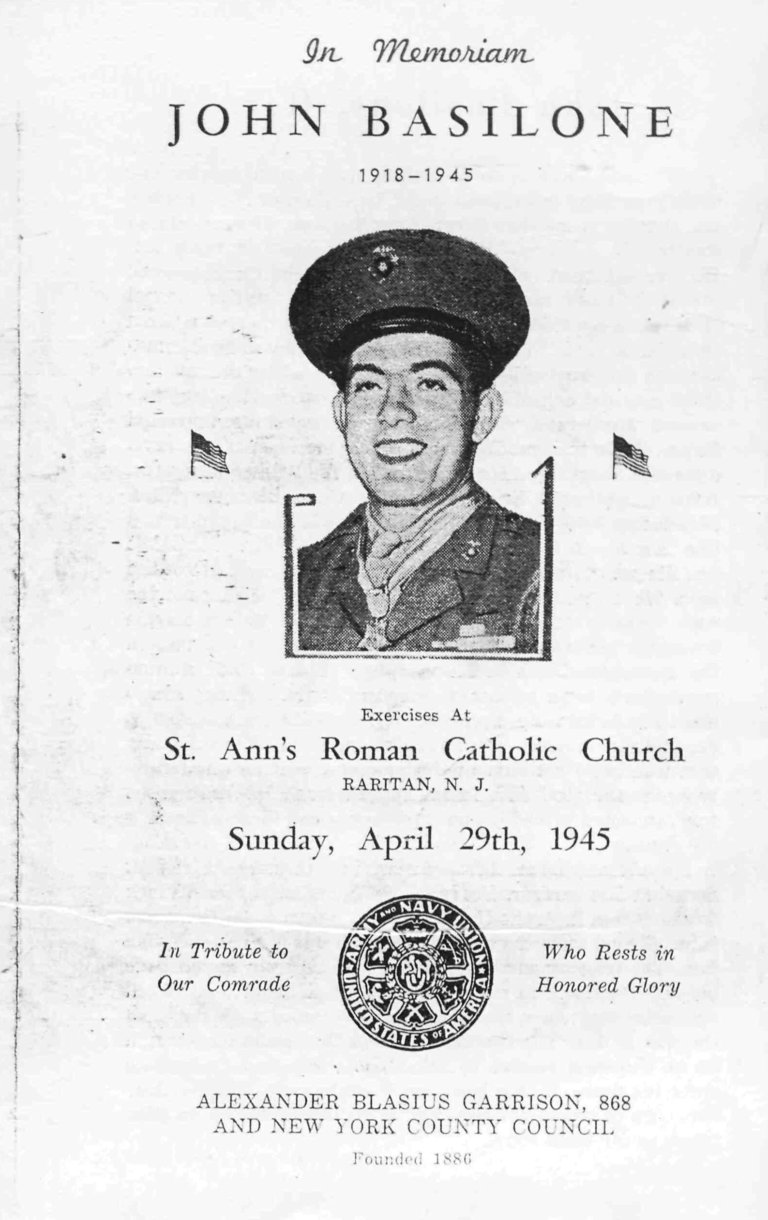

This Medal of Honor topic brings to life the valiant individuals who went above and beyond, and earned our nation’s highest honor. Many became well known in their time, and their names are still familiar to us today—names like John Basilone, Walt Ehlers, and Desmond Doss. But far too many of our nation’s heroes of the highest order are all but forgotten to anyone other than their families—men such as Cleto Rodriguez, Richard McCool, and Nicholas Minue. They are gone, but they shall not be forgotten.

Copied from the National WW II Museum Site.

Fritz

THE HISTORY OF THE MEDAL OF HONOR

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is our nation’s highest military award for valor. First authorized in 1861, in the 159 years since, 3,525 Medals of Honor have been bestowed upon American servicemen. The citations for the awards read as a “Who’s Who” of some of the bravest, most selfless, and at times, most sacrificial young men in America’s history. The Medal has a long history, and took many years to become the award held in such high regard as it is today.

In the early months of the American Civil War, the US military had no valor awards which could be given to soldiers or sailors distinguishing themselves in combat. In December 1861, a bill was passed in the Senate to authorize the production and awarding of “medals of honor” in an effort to “promote the efficiency of the Navy.” This first Medal could be awarded to enlisted sailors and Marines only. Thus, the Navy Medal of Honor was created. In February 1862, a similar bill was introduced to create a medal to be awarded to privates in the army who distinguished themselves. Later that year the bill was signed into effect, creating the US Army Medal of Honor.

Today, the Medal of Honor is known to be a rare award representing action of incredible valor or self-sacrifice. However, prior to World War I, the MOH was awarded much more frequently—nearly 3,000 times. Between 1861 and 1918, requirements for awarding the Medal of Honor and who could receive it gradually changed. The most significant changes allowed officers to receive the medal, applied “new standards” which meant the medal could not be awarded for “simple discharge of duty” but had to be for significant acts above and beyond those of others, and the recommendation had to have eyewitness testimony and could not be self-recommended.

In 1890, the Medal of Honor Legion was established with the responsibility of protecting the integrity of the Medal. Twenty-six years later, a Medal of Honor review board was created to review each Army Medal of Honor awarded prior to that year. There were increasing concerns that the Medal was being presented too easily, and that it had often been awarded for events not meriting such honor. After reviewing every Medal awarded until 1916, the review board decided to rescind 911 Medals, including the only one awarded to a woman—Civil War Assistant Surgeon Mary Walker. Walker’s Medal was rescinded due to her civilian status (it was reinstated in 1977 by President Jimmy Carter, making Walker the only female recipient).

A July 1918 Act of Congress laid the foundation for modern American military awards. The act provided for “lesser” awards, such as the Silver Star, thus giving a higher precedence to the Medal of Honor. The act also laid out an important requirement for the Medal: “the President is authorized to present, in the name of the Congress, a medal of honor only to each person who, while an officer or enlisted man of the Army, shall hereafter, in action involving actual conflict with an enemy, distinguish himself conspicuously by gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.” Thus, the Medal of Honor is sometimes referred to as the Congressional Medal of Honor.

During this period, the Army Medal was significantly redesigned. The new design for the medal was done by a recipient from the Civil War, General George Gillespie. This new version of the Medal became the now-iconic star surrounded by a green laurel, suspended from a pale blue ribbon with 13 white stars, and a bar bearing the word VALOR. The Navy Medal underwent only minor redesigns, but also switched to the blue ribbon with 13 stars. The Navy’s Medal has always hung from an anchor.

In World War II, many men went above and beyond the call of duty. There are 473 Medal of Honor recipients from the war. Their citations are full of heroics and sacrifice. Many of the Medals were awarded posthumously, in recognition of a life cut short. One of those is the Unknown Soldier who rests in the Tomb of the Unknown at Arlington Cemetery. The Medal was awarded among all ranks and rates—from Lieutenant General Jonathan Wainwright at the top all the way down to 18 year old Private Joseph Merrell.

Since the end of World War II, over two dozen Medals have been awarded to men who were denied the Medal during the war due to their race, ethnicity, or religion. In 1997, President Bill Clinton presented the Medal to seven African Americans who had been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Three years later, President Clinton presented 22 Japanese American veterans with the Medal of Honor. They too had been denied the honor during the war. In 2014, President Barack Obama presented the Medal to the “Valor 24,” individuals who had been denied based on race or religion. Of those, seven were World War II veterans. The latest Medal awarded for action in World War II was to US Army First Lieutenant Garlin Conner, whose Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the Medal. His widow, Pauline Conner, accepted the Medal on his behalf from President Donald Trump in 2018.

This Medal of Honor topic brings to life the valiant individuals who went above and beyond, and earned our nation’s highest honor. Many became well known in their time, and their names are still familiar to us today—names like John Basilone, Walt Ehlers, and Desmond Doss. But far too many of our nation’s heroes of the highest order are all but forgotten to anyone other than their families—men such as Cleto Rodriguez, Richard McCool, and Nicholas Minue. They are gone, but they shall not be forgotten.

Copied from the National WW II Museum Site.